December 23, 2022

TWITTER EXECUTIVES HAVE claimed for years that the company makes concerted efforts to detect and thwart government-backed covert propaganda campaigns on its platform.

Behind the scenes, however, the social networking giant provided direct approval and internal protection to the U.S. military’s network of social media accounts and online personas, whitelisting a batch of accounts at the request of the government. The Pentagon has used this network, which includes U.S. government-generated news portals and memes, in an effort to shape opinion in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Kuwait, and beyond.

The accounts in question started out openly affiliated with the U.S. government. But then the Pentagon appeared to shift tactics and began concealing its affiliation with some of these accounts — a move toward the type of intentional platform manipulation that Twitter has publicly opposed. Though Twitter executives maintained awareness of the accounts, they did not shut them down, but let them remain active for years. Some remain active.

The revelations are buried in the archives of Twitter’s emails and internal tools, to which The Intercept was granted access for a brief period last week alongside a handful of other writers and reporters. Following Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter, the billionaire starting giving access to company documents, saying in a Twitter Space that “the general idea is to surface anything bad Twitter has done in the past.” The files, which included records generated under Musk’s ownership, provide unprecedented, if incomplete, insight into decision-making within a major social media company.

Twitter did not provide unfettered access to company information; rather, for three days last week, they allowed me to make requests without restriction that were then fulfilled on my behalf by an attorney, meaning that the search results may not have been exhaustive. I did not agree to any conditions governing the use of the documents, and I made efforts to authenticate and contextualize the documents through further reporting. The redactions in the embedded documents in this story were done by The Intercept to protect privacy, not Twitter.

THE DIRECT ASSISTANCE Twitter provided to the Pentagon goes back at least five years.

On July 26, 2017, Nathaniel Kahler, at the time an official working with U.S. Central Command — also known as CENTCOM, a division of the Defense Department — emailed a Twitter representative with the company’s public policy team, with a request to approve the verification of one account and “whitelist” a list of Arab-language accounts “we use to amplify certain messages.”

“We’ve got some accounts that are not indexing on hashtags — perhaps they were flagged as bots,” wrote Kahler. “A few of these had built a real following and we hope to salvage.” Kahler added that he was happy to provide more paperwork from his office or SOCOM, the acronym for the U.S. Special Operations Command.

Twitter at the time had built out an expanded abuse detection system aimed in part toward flagging malicious activity related to the Islamic State and other terror organizations operating in the Middle East. As an indirect consequence of these efforts, one former Twitter employee explained to The Intercept, accounts controlled by the military that were frequently engaging with extremist groups were being automatically flagged as spam. The former employee, who was involved with the whitelisting of CENTCOM accounts, spoke with The Intercept under condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

In his email, Kahler sent a spreadsheet with 52 accounts. He asked for priority service for six of the accounts, including @yemencurrent, an account used to broadcast announcements about U.S. drone strikes in Yemen.

Around the same time, @yemencurrent, which has since been deleted, had emphasized that U.S. drone strikes were “accurate” and killed terrorists, not civilians, and promoted the U.S. and Saudi-backed assault on Houthi rebels in that country.

Other accounts on the list were focused on promoting U.S.-supported militias in Syria and anti-Iran messages in Iraq. One account discussed legal issues in Kuwait. Though many accounts remained focused on one topic area, others moved from topic to topic. For instance, @dala2el, one of the CENTCOM accounts, shifted from messaging around drone strikes in Yemen in 2017 to Syrian government-focused communications this year.

On the same day that CENTCOM sent its request, members of Twitter’s site integrity team went into an internal company system used for managing the reach of various users and applied a special exemption tag to the accounts, internal logs show.

One engineer, who asked not to be named because he was not authorized to speak to the media, said that he had never seen this type of tag before, but upon close inspection, said that the effect of the “whitelist” tag essentially gave the accounts the privileges of Twitter verification without a visible blue check. Twitter verification would have bestowed a number of advantages, such as invulnerability to algorithmic bots that flag accounts for spam or abuse, as well as other strikes that lead to decreased visibility or suspension.

KAHLER TOLD TWITTER that the accounts would all be “USG-attributed, Arabic-language accounts tweeting on relevant security issues.” That promise fell short, as many of the accounts subsequently deleted disclosures of affiliation with the U.S. government.

The Internet Archive does not preserve the full history of every account, but The Intercept identified several accounts that initially listed themselves as U.S. government accounts in their bios, but, after being whitelisted, shed any disclosure that they were affiliated with the military and posed as ordinary users.

This appears to align with a major report published in August by online security researchers affiliated with the Stanford Internet Observatory, which reported on thousands of accounts that they suspected to be part of a state-backed information operation, many of which used photorealistic human faces generated by artificial intelligence, a practice also known as “deep fakes.”

The researchers connected these accounts with a vast online ecosystem that included “fake news” websites, meme accounts on Telegram and Facebook, and online personalities that echoed Pentagon messages often without disclosure of affiliation with the U.S. military. Some of the accounts accuse Iran of “threatening Iraq’s water security and flooding the country with crystal meth,” while others promoted allegations that Iran was harvesting the organs of Afghan refugees.

The Stanford report did not definitively tie the sham accounts to CENTCOM or provide a complete list of Twitter accounts. But the emails obtained by The Intercept show that the creation of at least one of these accounts was directly affiliated with the Pentagon.

One of the accounts that Kahler asked to have whitelisted, @mktashif, was identified by the researchers as appearing to use a deep-fake photo to obscure its real identity. Initially, according to the Wayback Machine, @mktashif did disclose that it was a U.S. government account affiliated with CENTCOM, but at some point, this disclosure was deleted and the account’s photo was changed to the one Stanford identified as a deep fake.

The new Twitter bio claimed that the account was an unbiased source of opinion and information, and, roughly translated from Arabic, “dedicated to serving Iraqis and Arabs.” The account, before it was suspended earlier this year, routinely tweeted messages denouncing Iran and other U.S. adversaries, including Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Another CENTCOM account, @althughur, which posts anti-Iran and anti-ISIS content focused on an Iraqi audience, changed its Twitter bio from a CENTCOM affiliation to an Arabic phrase that simply reads “Euphrates pulse.”

The former Twitter employee told The Intercept that they were surprised to learn of the Defense Department’s shifting tactics. “It sounds like DOD was doing something shady and definitely not in line with what they had presented to us at the time,” they said.

Twitter did not respond to a request for comment.

“It’s deeply concerning if the Pentagon is working to shape public opinion about our military’s role abroad and even worse if private companies are helping to conceal it,” said Erik Sperling, the executive director of Just Foreign Policy, a nonprofit that works toward diplomatic solutions to foreign conflicts.

“Congress and social media companies should investigate and take action to ensure that, at the very least, our citizens are fully informed when their tax money is being spent on putting a positive spin on our endless wars,” Sperling added.

FOR MANY YEARS, Twitter has pledged to shut down all state-backed disinformation and propaganda efforts, never making an explicit exception for the U.S. In 2020, Twitter spokesperson Nick Pickles, in a testimony before the House Intelligence Committee, said that the company was taking aggressive efforts to shut down “coordinated platform manipulation efforts” attributed to government agencies.

“Combatting attempts to interfere in conversations on Twitter remains a top priority for the company, and we continue to invest heavily in our detection, disruption, and transparency efforts related to state-backed information operations. Our goal is to remove bad-faith actors and to advance public understanding of these critical topics,” said Pickles.

In 2018, for instance, Twitter announced the mass suspension of accounts tied to Russian government-linked propaganda efforts. Two years later, the company boasted of shutting down almost 1,000 accounts for association with the Thai military. But rules on platform manipulation, it appears, have not been applied to American military efforts.

The emails obtained by The Intercept show that not only did Twitter whitelist these accounts in 2017 explicitly at the behest of the military, but also that high-level officials at the company discussed the accounts as potentially problematic in the following years.

In the summer of 2020, officials from Facebook reportedly identified fake accounts attributed to CENTCOM’s influence operation on its platform and warned the Pentagon that if Silicon Valley could easily out these accounts as inauthentic, so could foreign adversaries, according to a September report in the Washington Post.

Twitter emails show that during that time in 2020, Facebook and Twitter executives were invited by the Pentagon’s top attorneys to attend classified briefings in a sensitive compartmented information facility, also known as a SCIF, used for highly sensitive meetings.

“Facebook have had a series of 1:1 conversations between their senior legal leadership and DOD’s [general counsel] re: inauthentic activity,” wrote Yoel Roth, then the head of trust and safety at Twitter. “Per FB,” continued Roth, “DOD have indicated a strong desire to work with us to remove the activity — but are now refusing to discuss additional details or steps outside of a classified conversation.”

Stacia Cardille, then an attorney with Twitter, noted in an email to her colleagues that the Pentagon may want to retroactively classify its social media activities “to obfuscate their activity in this space, and that this may represent an overclassification to avoid embarrassment.”

Jim Baker, then the deputy general counsel of Twitter, in the same thread, wrote that the Pentagon appeared to have used “poor tradecraft” in setting up various Twitter accounts, sought to potentially cover its tracks, and was likely seeking a strategy for avoiding public knowledge that the accounts are “linked to each other or to DoD or the USG.” Baker speculated that in the meeting the “DoD might want to give us a timetable for shutting them down in a more prolonged way that will not compromise any ongoing operations or reveal their connections to DoD.”

What was discussed at the classified meetings — which ultimately did take place, according to the Post — was not included in the Twitter emails provided to The Intercept, but many of the fake accounts remained active for at least another year. Some of the accounts on the CENTCOM list remain active even now — like this one, which includes affiliation with CENTCOM, and this one, which does not — while many were swept off the platform in a mass suspension on May 16.

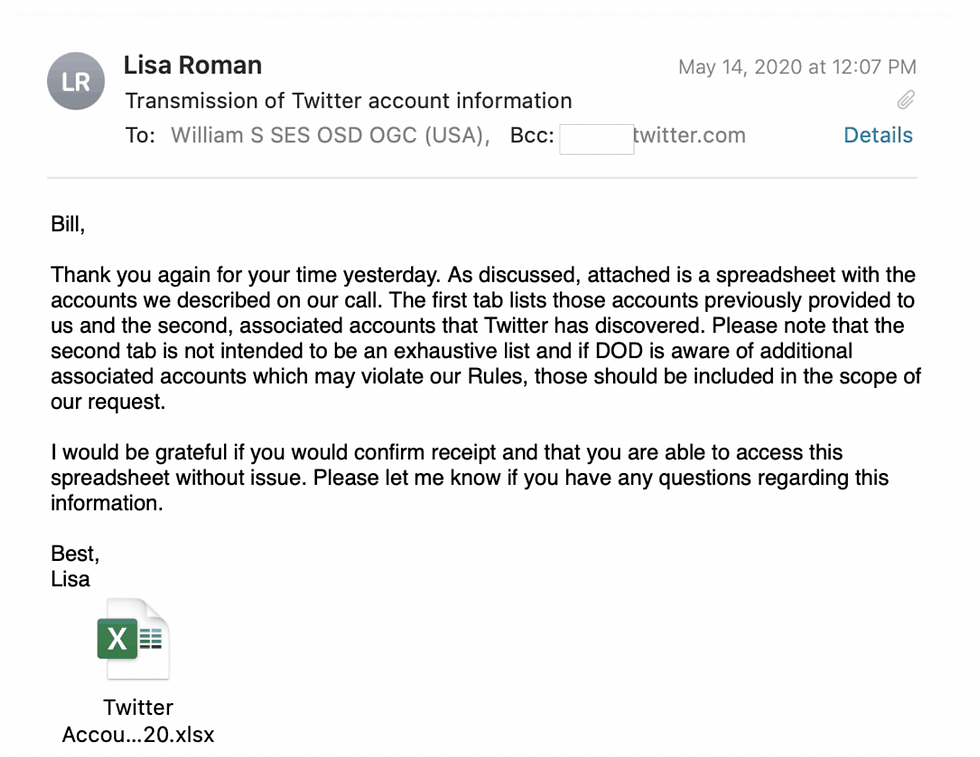

In a separate email sent in May 2020, Lisa Roman, then a vice president of the company in charge of global public policy, emailed William S. Castle, a Pentagon attorney, along with Roth, with an additional list of Defense Department Twitter accounts. “The first tab lists those accounts previously provided to us and the second, associated accounts that Twitter has discovered,” wrote Roman. It’s not clear from this single email what Roman is requesting – she references a phone call preceding the email — but she notes that the second tab of accounts — the ones that had not been explicitly provided to Twitter by the Pentagon — “may violate our Rules.” The attachment included a batch of accounts tweeting in Russian and Arabic about human rights violations committed by ISIS. Many accounts in both tabs were not openly identified as affiliated with the U.S. government.

Twitter executives remained aware of the Defense Department’s special status. This past January, a Twitter executive recirculated the CENTCOM list of Twitter accounts originally whitelisted in 2017. The email simply read “FYI” and was directed to several Twitter officials, including Patrick Conlon, a former Defense Department intelligence analyst then working on the site integrity unit as Twitter’s global threat intelligence lead. Internal records also showed that the accounts that remained from Kahler’s original list are still whitelisted.

Following the mass suspension of many of the accounts this past May, Twitter’s team worked to limit blowback from its involvement in the campaign.

Shortly before publication of the Washington Post story in September, Katie Rosborough, then a communications specialist at Twitter, wrote to alert Twitter lawyers and lobbyists about the upcoming piece. “It’s a story that’s mostly focused on DoD and Facebook; however, there will be a couple lines that reference us alongside Facebook in that we reached out to them [DoD] for a meeting. We don’t think they’ll tie it to anything Mudge-related or name any Twitter employees. We declined to comment,” she wrote. (Mudge is a reference to Peiter Zatko, a Twitter whistleblower who filed a complaint with federal authorities in July, alleging lax security measures and penetration of the company by foreign agents.)

After the Washington Post’s story published, the Twitter team congratulated one another because the story minimized Twitter’s role in the CENTCOM psyop campaign. Instead, the story largely revolved around the Pentagon’s decision to begin a review of its clandestine psychological operations on social media.

“Thanks for doing all that you could to manage this one,” wrote Rebecca Hahn, another former Twitter communications official. “It didn’t seem to get too much traction beyond verge, cnn and wapo editors promoting.”

CENTCOM did not initially provide comment to The Intercept. Following publication of this story, CENTCOM’s media desk referred The Intercept to Brigadier Gen. Pat Ryder’s comments in a September briefing, in which he said that the Pentagon had requested “a review of Department of Defense military information support activities, which is simply meant to be an opportunity for us to assess the current work that’s being done in this arena, and really shouldn’t be interpreted as anything beyond that.”

THE U.S. MILITARY and intelligence community have long pursued a strategy of fabricated online personas and third parties to amplify certain narratives in foreign countries, the idea being that an authentic-looking Persian-language news portal or a local Afghan woman would have greater organic influence than an official Pentagon press release.

Military online propaganda efforts have largely been governed by a 2006 memorandum. The memo notes that the Defense Department’s internet activities should “openly acknowledge U.S. involvement” except in cases when a “Combatant Commander believes that it will not be possible due to operational considerations.” This method of nondisclosure, the memo states, is only authorized for operations in the “Global War on Terrorism, or when specified in other Secretary of Defense execute orders.”

In 2019, lawmakers passed a measure known as Section 1631, a reference to a provision of the National Defense Authorization Act, further legally affirming clandestine psychological operations by the military in a bid to counter online disinformation campaigns by Russia, China, and other foreign adversaries.

In 2008, the U.S. Special Operations Command opened a request for a service to provide “web-based influence products and tools in support of strategic and long-term U.S. Government goals and objectives.” The contract referred to the Trans-Regional Web Initiative, an effort to create online news sites designed to win hearts and minds in the battle to counter Russian influence in Central Asia and global Islamic terrorism. The contract was initially carried out by General Dynamics Information Technology, a subsidiary of the defense contractor General Dynamics, in connection with CENTCOM communication offices in the Washington, D.C., area and in Tampa, Florida.

A program known as “WebOps,” run by a defense contractor known as Colsa Corp., was used to create fictitious online identities designed to counter online recruitment efforts by ISIS and other terrorist networks.

The Intercept spoke to a former employee of a contractor — on the condition of anonymity for legal protection — engaged in these online propaganda networks for the Trans-Regional Web Initiative. He described a loose newsroom-style operation, employing former journalists, operating out of a generic suburban office building.

“Generally what happens, at the time when I was there, CENTCOM will develop a list of messaging points that they want us to focus on,” said the contractor. “Basically, they would, we want you to focus on say, counterterrorism and a general framework that we want to talk about.”

From there, he said, supervisors would help craft content that was distributed through a network of CENTCOM-controlled websites and social media accounts. As the contractors created content to support narratives from military command, they were instructed to tag each content item with a specific military objective. Generally, the contractor said, the news items he created were technically factual but always crafted in a way that closely reflected the Pentagon’s goals.

“We had some pressure from CENTCOM to push stories,” he added, while noting that he worked at the sites years ago, before the transition to more covert operations. At the time, “we weren’t doing any of that black-hat stuff.”

Update: December 20, 2022, 4:17 p.m. This story has been updated with information provided by CENTCOM following publication.

SOURCE: The Intercept

Comments