February 1, 2021 | 9:57am | Updated

NORTON SHORES, MI – Brennan Dethloff could always count on hockey to help him in his battle with depression and anxiety.

But when the coronavirus pandemic took hockey away, it was too much for Brennan to take.

The 18-year-old senior at Mona Shores High School died Jan. 18. His parents believe his death was linked to his depression.

Brennan was excited to be back on the Sailors’ varsity hockey team this season. Slipping on that No. 22 sweater alongside his teammates meant everything to him, said his parents, Brian and Rona Dethloff. His hockey team was an extension of family and it carried a far greater impact than any win or loss ever could.

It was his outlet.

RELATED: Coronavirus pause causes concerns of mental toll on high school athletes

But once winter high school contact sports seasons were pushed back not once, but twice, that in turn pushed Brennan close to his breaking point, according to his parents.

“You could see it in his face and his body language and his demeanor that it just took it out of him. We both noticed it and did what we could and … ultimately that night, something set him off,” said Brian Dethloff. “You know, unfortunately, he chose to do what he did.”

In the days since Brennan’s death, the Dethloffs have been filled with grief and they search for explanations as to why high school sports and young people’s lives are still being interrupted even though coronavirus numbers are on the decline.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services has barred ice hockey, boys and girls basketball, wrestling and competitive cheer from competition. All winter contact sports are only allowed to perform non-contact activity during team practices. Until Jan. 22, winter contact sports were set to resume in full capacity on Feb. 1. However, the MDHHS extended those orders until Feb. 21. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer said high school sports could return in a matter of “weeks or days.”

During a virtual press conference Friday, Michigan High School Athletic Association executive director Mark Uyl said he believes that now is the right time to take the next step and allow those aforementioned four winter sports to begin immediately.

While the Dethloffs say they are proponents of the “Let Them Play” movement, which is a voice of students, coaches, administrators, parents and fans who want the games to go on, they are trying to be careful as to not point a finger in blame at any specific person or group.

An emotional Rona Dethloff said she wishes Brennan could have realized how loved he was and how much he meant to others, but he carried a burden and pain in his heart.

“We want people to know that they shouldn’t be ashamed of (depression and anxiety) and that they should talk about it and get help if they need the help,” she said.

On the surface, Brennan Dethloff seemed to have everything going for him. School came easy and he carried a 3.8 grade-point average. Sports came more difficult, but he worked for his spot on the Mona Shores hockey team as a gritty defenseman who had his teammates’ backs. His parents described him as an extrovert, who enjoyed playing disc golf and video games with buddies, as well as hunting, fishing and jet skiing. He would go for beach drives as a means of escape.

Brennan’s No. 1 quality was the way he looked out for others before himself, according to his parents, but it also came as a detriment. It was difficult to tell how much he was hurting on the inside.

His parents knew it, but others may not have recognized it.

“You always think, ‘What could we have done different?’ or ‘What didn’t he have that would have helped?’ It wasn’t anything about that. It was about, he truly had a depression issue and we helped as much as we could,” Brian Dethloff said.

“But, at the end of the day, everyone on the outside thought he had everything going for him and ‘What did he have to worry about?’ So, I think that’s what the message really is: You don’t know what somebody’s going through. You don’t know everybody’s backstory.

Last year, Brennan got a tattoo over his ribcage that read “WARR;OR.” His mother’s stepbrother, Luke Forton, is a tattoo artist and he did the work. The semicolon in place of the letter “i” in the tattoo was the focal point, a symbol of solidarity designed to fight the stigma around suicide, depression and mental-health issues.

As Rona Dethloff stated, a period ends a sentence, while a semicolon means you’re not done – you continue on, and your story is not over.

Brian Dethloff said his son was a warrior, and that the tattoo was a constant reminder of that when Brennan looked in the mirror at himself.

“An important thing for me, and I said it a while back, we never wanted his depression or his anxiety to define who he was, you know. He was so much more than that,” Rona Dethloff said as tears filled her eyes and she became choked up. " … But it was a part of him and, you know, we weren’t ashamed of it.

“It’s nothing to be ashamed of – there’s so many kids struggling right now and it’s not their fault,” she continued, emphasizing that point through inflection. “You know, they don’t ask for it – they didn’t ask for anything that’s happened this last year and there’s so many people who will listen and who will do so much for them, but they just have to … they have to reach out and it’s hard – it’s hard to tell people that you’re struggling and that things aren’t as perfect as they might seem and that you want everybody to believe that they are. So I think it was easier for him to kind of pretend things were OK – you know, help everybody else and pretend he was fine.”

Carter Dethloff is not pretending everything is fine. He looked up to his older brother. Even though they were opposites in many ways, there was a mutual admiration and respect. They loved each other.

Carter, 16, is a tall, athletically gifted goaltender, who played Triple-A hockey for the last four years. He opted to join the Mona Shores team this season so that he could play hockey with Brennan for his senior year. He will not get that chance now, regardless of when or if the puck drops on the Sailors’ season.

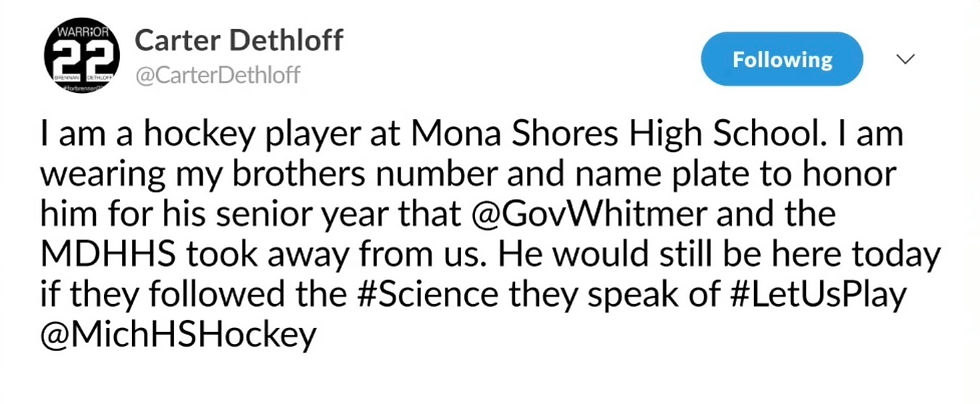

One week after his brother’s passing, Carter Dethloff tweeted that he was going to honor his brother this season by wearing No. 22 and his brother’s nameplate.

“It will mean the world to me – it’s playing for something, someone, more than just playing the game,” Carter said. “He was someone I could trust as a player and someone that you could come to and just trust.”

Carter also had some strong words in the tweet directed at the decision-makers, calling into question the “science” being used and hopping on board the “Let Them Play” movement.

“Let Them Play” is hosting a rally at noon today at the State Capitol. The organization is urging the state to reconsider and re-open all winter sports.

Brian Dethloff is confounded by what he sees as a lack of transparency when it comes to the decision making behind suspending high school sports and he said some groups do not understand the ramifications and mental-health impact that those interruptions are having.

“You can call any one of your local health departments, mental health departments, Health West or wherever you’re at, and they’ll tell you the stats. They’re there and it’s unbelievable the difference it’s been over the last year and actually the last six months, the amount of cases of depression and suicide. Where are those numbers? They don’t show ‘em,” he said.

“We want (Brennan’s) story to help shine a light on what is actually going on. … What he needed was what all these kids needed -- a little bit back to normalcy and to get his life back.”

The Dethloffs have been moved by the outpouring of support from the community, family and friends.

More than 1,000 people attended Brennan’s visitation, while 340 showed up for his funeral and 150 more watched live online.

From the Mona Shores hockey team posting on Facebook a plea for people to place a hockey stick on their porches in honor of Brennan, to the Sailors’ football team wearing helmet decals remembering Brennan during their state championship game last Friday at Ford Field, to dozens of hockey players from nearby schools showing support outside the church, plenty of love was shown for Brennan.

He always looked out for others, but now it was time for an entire community to wrap its collective arms around Brennan’s loved ones.

Brian Dethloff knows his family has a difficult road ahead, but he takes some solace in the fact that Brennan will continue to watch over them.

Friday, Carter looked out the window as his father spoke about his brother and saw a cardinal in the backyard.

“(Brennan is) listening,” Rona Dethloff told Carter with a reassuring tone.

It wasn’t the first indicator that Brennan is still with them in spirit, according to Brian Dethloff.

“Rona was down in the hot tub down below our deck a couple nights ago, or last week. She was down there by herself, the lights off, fire was on, talking to Brennan,” Brian Dethloff said. “When she got out – we have lights that line underneath the deck and they weren’t on – and as she was leaving one light just flashed. Not all of them, she didn’t turn them on – one flashed and that was it. … Just saying, ‘I’m here with you, I heard you.’”

In lieu of flowers, the “Brennan Dethloff Memorial Scholarship Fund” has been set up at ChoiceOne Bank, 1030 W. Norton Ave., Muskegon, MI 49441.

Anyone in suicidal crisis or emotional distress can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, which is a 24/7 service.

Comments